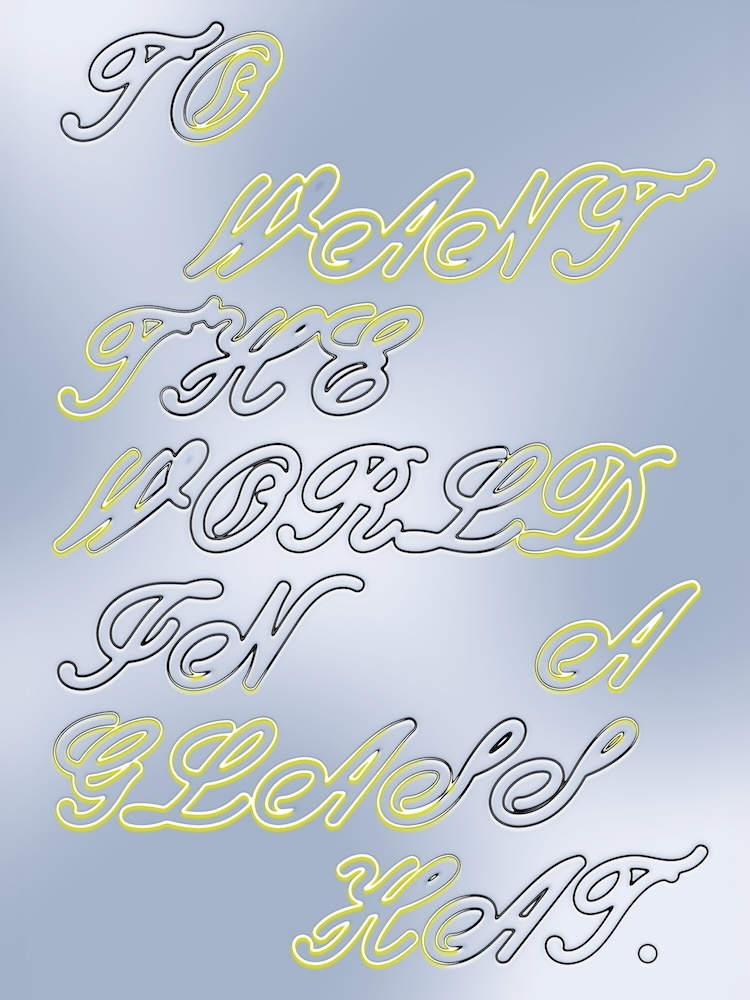

TO WANT THE WORLD IN A GLASS HAT.

BETHAN HUGHES

DOMINIQUE HURTH

Opening

Opening, Fri, Dec 13, 2024, 5-9pm

Location / Opening hours

Neun Kelche, Pasedagplatz 3-4 (access via “An der Industriebahn”), 13088 Berlin

Opening hours, from Jan 10: Fridays, 2-7pm and by appointment

Exhibition

Dec 13, 2024 – Mar 2, 2025

Further collaborations

Reading group in collaboration with Diffrakt, Berlin, Feb 14, 2025

Finissage, Mar 1, 2025, 4-9pm

Sound Salon by Emilie Ding and Alizée Lenox, Mar-Apr, 2025

NEW YEAR ON DARTMOOR

This is newness: every little tawdry

Obstacle glass-wrapped and peculiar,

Glinting and clinking in a saint’s falsetto. Only you

Don’t know what to make of the sudden slippiness,

The blind, white, awful, inaccessible slant.

There’s no getting up it by the words you know.

No getting up by elephant or wheel or shoe.

We have only come to look. You are too new

To want the world in a glass hat.

—Sylvia Plath

TO WANT THE WORLD IN A GLASS HAT.

DISPLAY_ The spark for this project to take shape —and the convergence of your works— stemmed from Sylvia Plath’s poem New Year on Dartmoor, written between 1961 and 1962 and published in 1981. The exhibition’s title, To want the world in a glass hat., is drawn from the poem’s final line. Bethan, how did this poem emerge in your discussions with Dominique while preparing for the show?

BETHAN_ By chance! My mum, Janet, sent me the poem several years ago. She’s retired now but she used to be an English literature teacher. She and her brother were the first people in our family to go to university at a time when it was free for those from a low income background. The poem stuck with me. There is something very particular in the way Plath merges lightness and sensuality (newness, glass-wrapped, glinting and clinking) with unbearability (obstacle, tawdry, blind, white, awful, inaccessible). After visiting Neun Kelche one day, it came to mind again. I shared it with Dominique and it immediately resonated as a way to think through the architecture of the space, materiality and voice. I love the idea of the words and the sounds they make being passed on, again and again, transforming as they travel through new materials and bodies while maintaining a rec- ognisable waveform that links them back to the original.

For me, Plath creates a visceral landscape through reference to seemingly everyday materials and objects (elephant, wheel, boot). Thinking with and through materials about their entangled histories and political meanings, and the often cumbersome process of transforming them into sculptures or installations, is central to my practice. Though her work has since been canonized in (mainly white) feminist circles, Plath was marginalised in her time. The posthumous poetry volume that New Year on Dartmoor appears in is ed- ited by Ted Hughes, the prototypical male genius to whom Plath was married, which represents both an act of display but also filtering of Plath’s word/voice through him. The 9K space is dominated by huge windows which create a vitrine-like effect (“We have only come to look”). The idea to acti- vate these glass surfaces using transducer speakers arrived immediately as they allow whole surfaces to become sound bodies. I wanted to play with this idea of dispersal, of filtering, of glass as a source and site for voice.

DISPLAY_How does Sylvia Plath’s poem resonate with your works, both within the context of the exhibition and more broadly?

BETHAN_For me, Plath creates a visceral landscape through reference to seemingly everyday materials and objects (elephant, wheel, boot). Thinking with and through materials about their entangled histories and political meanings, and the often-cumbersome process of transforming them into sculptures or installations, is central to my practice. Though her work has since been canonized in (mainly white) feminist circles, Plath was marginalised in her time. The posthumous poetry volume that New Year on Dartmoor appears in is edited by Ted Hughes, the prototypical male genius to whom Plath was married, which represents both an act of display but also filtering of Plath’s word/voice through him. The 9K space is dominated by several huge windows which create a vitrine-like effect (“We have only come to look”). The idea to activate these glass surfaces using transducer speakers arrived immediately as I had recently used the same technology in a piece which tells the story of a plant from the perspectives of multiple women across time (Hevea Act 6: An Elastic Continuum, 2023). Whereas with traditional speakers the sound comes from a fairly localised source, transducer speakers allow whole surfaces to become sound bodies. I wanted to play with this idea of dispersal, of filtering, of glass as a source and site for voice.

DISPLAY_ The themes of newness and renewal are central to the poem as well. I see newness here as an inherent part of transformation, guiding us toward renewal. However, it can also lead us into the unknown, which can feel alienating or destabilizing. At the same time, there are small details— imperfect and sometimes uncomfortable—that contribute to the beauty of change. What are your thoughts, 9K? How can we view the exhibition through this lens?

NEUN KELCHE_ This exhibition marks a turning point for us. For the first time, we are cooperating with another pro- ject space and bringing together two female artists by curating their work in relation to each other. Project spaces are currently in great danger. How much newness can we still generate when we are running out of resources due to recent cuts and gradually losing the strength to fight under the current circumstances? The exhibition takes place against the backdrop of a culturally and politically decisive turning point in Berlin’s yearly cycle—by 2025, we won’t even know whether and how we can con- tinue to exist as a space. Sylvia Plath also wrote about a New Year’s transition. It feels as if a giant bell jar has been placed over Berlin, causing time in the cultural scene to stand still, as we still don’t fully understand the impact of this year’s political decisions. This makes it all the more important for us to connect with others in the cultural field and pool our energies.

DISPLAY_How do you interpret the final line of the poem: “To want the world in a glass hat.”?

To me, it evokes something both fragile and beautiful—transparent yet confining. It suggests a desire to preserve one’s surroundings, or life itself in a controlled, museum-like way: perfect to observe, but distant from real experiences. Or could it instead speak to processes of exclusion, where certain elements are deliberately kept apart or inaccessible? The invisible barrier or isolation?

BETHAN_A hat is something you can hold in your hands (or wear on your head!), that you can turn around and consider from all possible angles, allowing you to gain an overview of it and maybe, then, to understand it. It is impossible to hold, comprehend, the complexity of the world and folly to even attempt or desire such a thing (There’s no getting up it by the words you know). Yet we are condemned to try to hold, to describe. The world in a glass hat is a perfect oxymoron! It is a wonderfully ambiguous line.

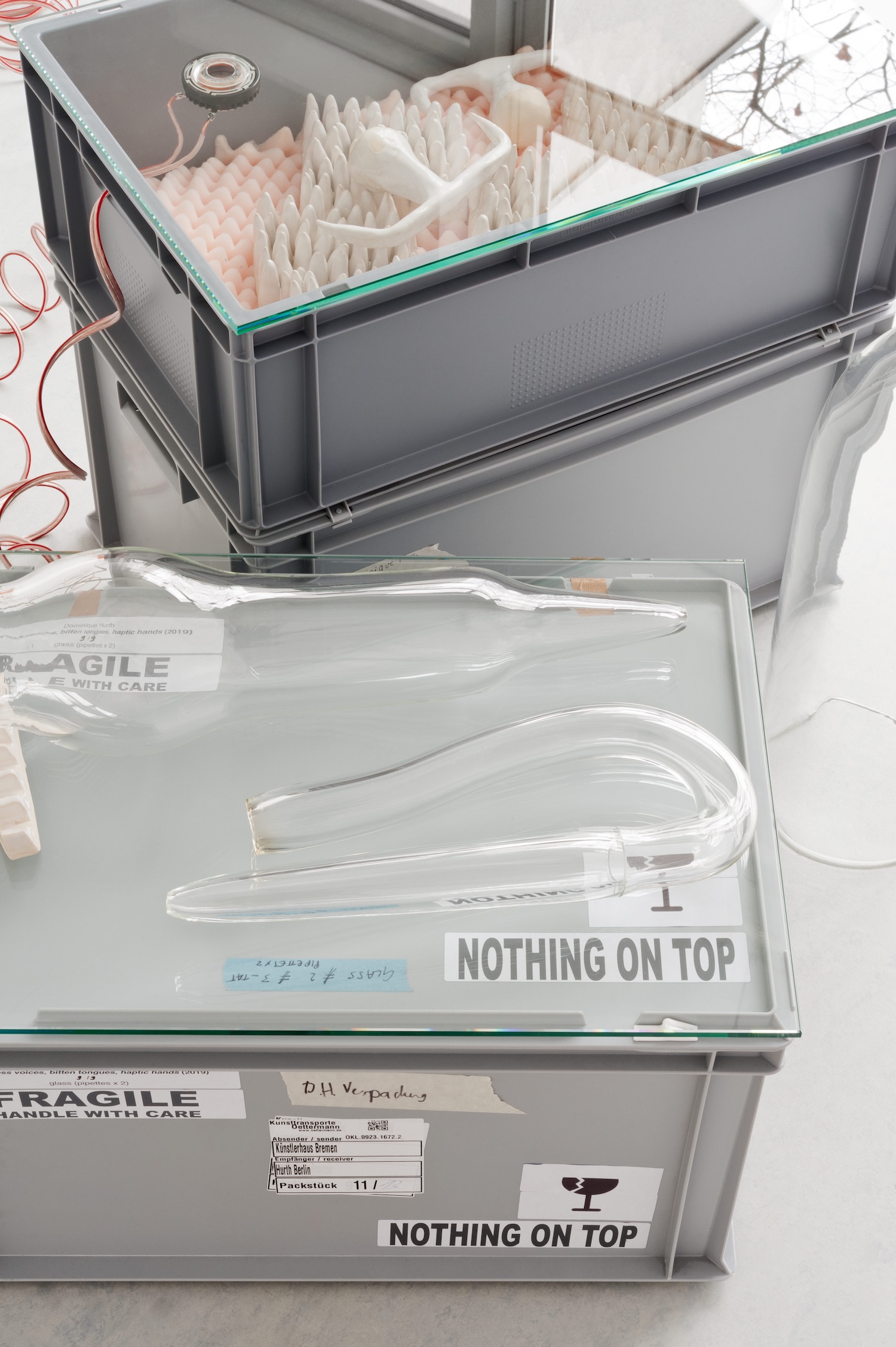

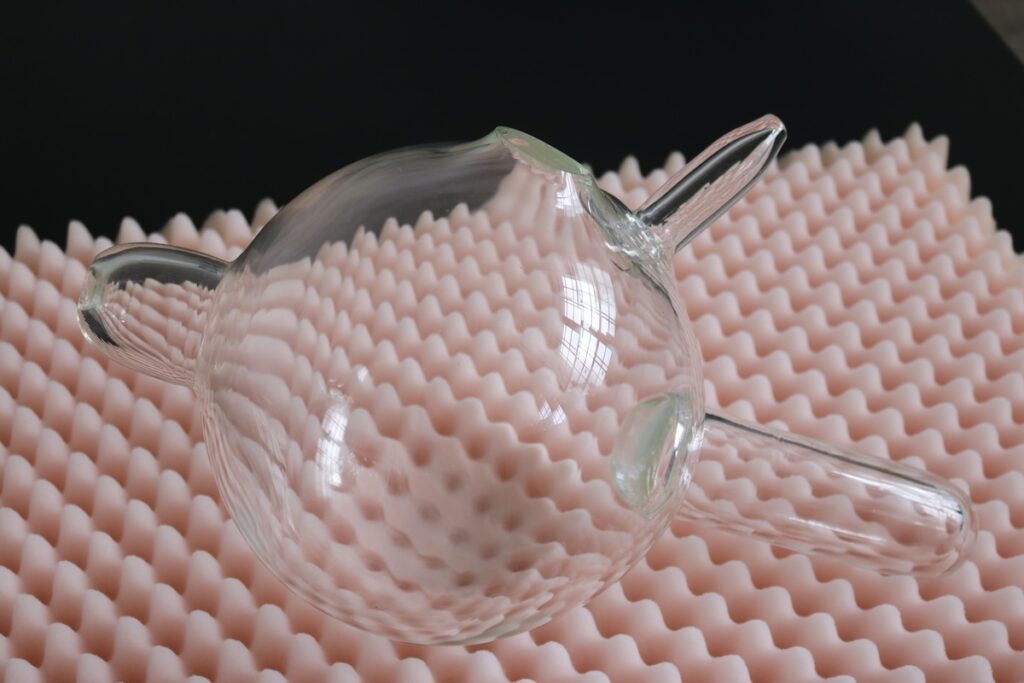

DISPLAY_ Dominique, in your work soundless voices, bitten tongues, haptic hands (2019), you use glass both as a material and a thematic element. Could you share more about this piece? What research informed its development, and how did you approach the fabrication process?

DOMINIQUE_ This work developed after an invitation by Felix Sattler of the Tieranatomisches Theatre (Berlin, on the Charité Campus) back in 2018 and took as a starting-point the biographies of some objects held at the collection of historical physical instruments of the Humboldt University in Berlin-Adlershof, and scientific objects between the 19th and 20th centuries at large. I focused especially on objects held in hands, or brought to the mouth (such as the pipette), used by women, and intertwined them directly with their fields of usage and with the biographies of three women who have often been ignored or forgotten in official histori- ography (Lise Meither, Elsa Neumann, Lydia Rabinowitsch-Kempner). Those three scientists stood for groundbreaking research into physics and microbiology : Meitner formulated the theory of nuclear fission, Rabinotiwsch-Kempner described the transmission of tuberculosis and was the first woman to be appointed professor in Berlin, Neumann was the first woman in Berlin to receive a PhD in physics – many firsts, yet there was and still is too little known or remembered about them. The historical objects became tools to speak about muteness and silenced voices.

As often in my work, I use the strategy of replicating and rebuilding the objects of my attention, by altering their scale and enhancing or decreasing details, and the chosen material always originates from the research itself. The sculptures here are augmented replicas of some instruments for physics preserved behind the glass of the vitrine, or the glass of the negative that I observed in scientific archives (Humboldt-Universität, Archives of the Max Planck Society in Berlin-Dahlem and the Churchill Archives Centre in Cambridge). The objects thus became sculpturally transformed in their materiality of the blown-glass. The use of glass here is clearly referencing the material the objects were originally made of and thus questioning the in- formation the material itself contains within. Furthermore, I was interested in the form-shaping of the process-making with blown glass: air gets blown into the raw material in order to give it a form, it breathes through the material, it captures the raw material and finds its shape in a meticulous schedule of liquefaction. It is air that is sealed in them, and in the performative part of the work, it is air (through language) that activates the objects anew. The objects I was looking at in the archives and collections were phenomenologically seen no objects any longer, they were preserved behind the glass of the vitrine, or the glass of the negative, but were not. In their transformation into the material and the handling of the objects through the performance, they were negotiated and able to speak again.

DISPLAY_ Architectures are often shaped by the standards and norms dictated by urban planning over time, many of which are imbued with underlying ideologies. A striking example is the book Architect’s Data (Bauentwurfslehre, published first 1936), which served as a key reference for build- ing typologies and spatial requirements for architecture in 20th-century Germany and worldwide. It nourished the re- search for your piece Accurate to Standards, Well-proportioned, Finely structured (2021), Dominique. Could you share how you approached the composition of this work? What considerations guided your choices, particularly the choice of fabric?

DOMINIQUE_This installation was originally developed site-specifically for a solo exhibition in a small kiosk in the city of GIeßen that is used now as an art institution. I became obsessed with the facade of the building and the date of the building’s construction, 1937, a year after the publication of Ernst Neufert’s Bauentwurfslehre (a handbook on architecture that is still regarded internationally as a standard work). The 20-metre-long drawing on fabric is a composition of brick-building works as defined by Neufert in the guide of 1936. I wanted to question the problematic history of standardization and rationalization of architectural buildings (that Neufert coined) and sharpen the eye for details that don’t quite fit when it comes to architecture, as well as highlight the amnesia of architectural history when it comes to its intertwinement with national-socialist and fascist ideologies and its continuities after 1945. The fabric was chosen to “dress” the interior of the building, in the most classical sense of interior design, while the hand-drawing becomes fluid and imprecise when imposed on the soft material of the fabric. The softness of the material was responding to the rigidity of the architecture, it was also counteracting the strict male-alike rigidity of the norm. The line deviates, the folds inform the architectural guide, the norm expels – it becomes a score to question what is not fitting in the norm, what deviates from the expected form.

NEUN KELCHE_Marie, both our project spaces have a large window front as a key part of their architecture. There is a sort of permeability that comes with this. Now that Display is a nomadic initiative, how did you feel about conceiving this exhibition for another physical project space in Berlin and how do you connect the notion and vision of Display to Neun Kelche?

DISPLAY_When I started Display at the end of 2015, the name arose exactly from the idea of considering the entire space as an exhibition display. The large glass window made it possible for processes and transformations to be visible, to put them on display. Including this window case was also a way to ensure accessibility and allow a perspective from outside. It evolved as a project space in this 30m2 former commercial premise at Mansteinstr. 16 until 2020. I’ve been very interested in ways of thinking about space, architecture and spatiality–particularly through the encounters of different bodies in space. So of course, this specific site informed my curatorial practice and since it had many architectural features (two steps “cutting” the space, a corner, the large window, etc.), it was also very playful. Now without having a fixed location I like a lot to bring these thoughts through the different collaborations and the various places. At Neun Kelche, I think we also share this way of working with the architectural space as an active agent with which to compose and negotiate.

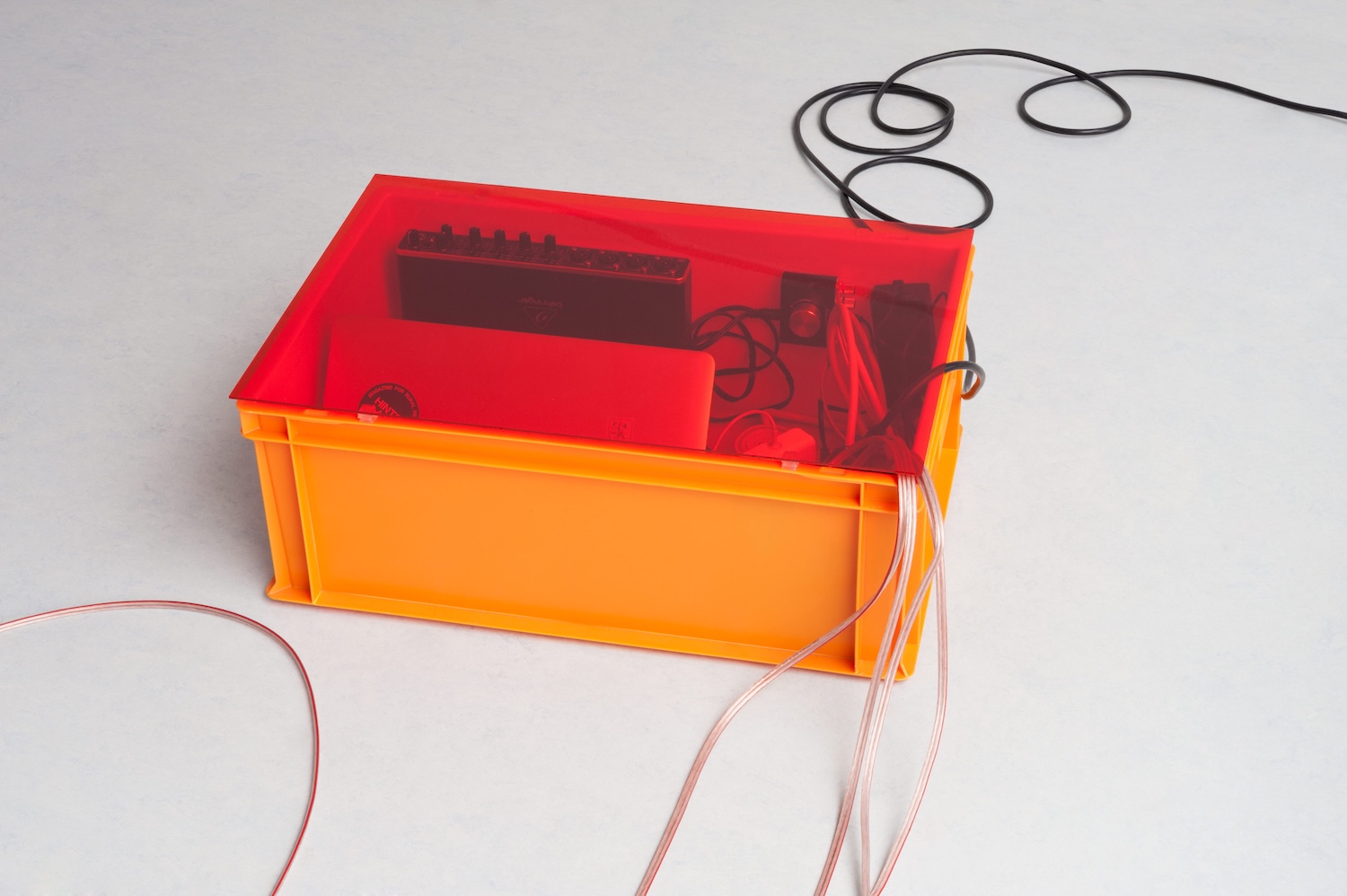

DISPLAY_Your sound piece Bethan fills the space and invites visitors to activate their listening skills in the exhibition too. What do we hear? How did you process and how did you compose your piece?

BETHAN_The basis for the piece is a 30-minute-long audio recording that I made from inside my apartment on New Year’s Eve in 2022. I live in a place called the “High-Deck-Siedlung” which is at the end of Sonnenallee in Neukölln. It is a place that is often portrayed in the popular press as a problem area, in articles where the phrase ‘Sozialer Brennpunkt’ communicates a thinly veiled racism. The architecture is characterised by long, low concrete Plattenbau. Like an alarm clock that rings just once a year, Berlin collectively erupts on Sylvester; for three years in a row during the pandemic, I experienced the celebrations from inside my apartment on the High-Deck. The multilayered sounds of exploding, fizzing, and whirling fireworks arrive from every direction, bounce off the angular concrete structures, and are filtered through the thick walls and glass windows of the apartment. I worked with Diego Flórez, a filmmaker and artist who is a longtime collaborator, to ‘glassify’ these recordings. We worked on maintaining the complexity of the audio but tried to transform it into something sharper, more fragile and ambiguous. In addition, I used a contact microphone to record lots of moments of manipulating glass: scraping, sliding, scoring, splashing, stroking. I also experimented with smashing but the sounds were far less interesting than those which balanced on the edge of breaking. Inspired by Dominique’s Accurate to Standards piece, which can be read as a graphic musical score in seven parts, I decided to divide the audio into seven phases. Embedded within one of the display cases, a perpetually ticking yet faulty metronome that misses and doubles beats is the fourth channel.

DISPLAY_ We began our collaboration by discussing archives—particularly artists’ archives—the challenges of preserving certain materials like textile works, and the role of storage systems as an integral part of an artist’s practice. We also explored the idea of “actualizing” or recontextualizing works, especially by presenting them in their stored state. Building on this, we were drawn to the idea of show- casing existing works.

NEUN KELCHE_ Neun Kelche used to be the storage of a supermarket, Kaiser’s. Now, it has become a space of con- temporary art. As a project space we often ask ourselves, what dimensions of art production can be shown in a project space. We ask artists to show existing works, but often they want to create something new when given the chance to produce something for such a big space. For this exhibi- tion we talked a lot about the art making process itself and, in the end, we are showing two already existing works by Dominique Hurth, directly taken out of the storage and one new production by Bethan Hughes.

DISPLAY_ Dominique, what does it mean to you to show the works in this new context? How do they acquire new meanings when proposed as archival pieces and are in correspondence with Bethan’s work?

DOMINIQUE_ Both works were developed in direct response to the histories of the exhibition spaces the works were meant to be first shown in, and both works are only shown here partially: each work has more components to it, so we are only looking at “partially unveiled” components of two larger installations. While the glass and ceramic sculptures have been shown in other exhibition spaces (as a whole), the fabric drawing has not been shown yet in another exhibition context, which is to me quite unusual. While I often respond to the history or the architecture of the exhibition space, I am really used to having my works being shown again in other exhibition contexts. I love seeing the works being shown in dialogue with other pieces, which is also a privilege of working within the context of curated exhibitions, and then there are those moments of “care” happening in between: packing, unpacking, repacking the works for instance. Some works are not coming back to the studio or the storage in be- tween but simply have their life by themselves. They carry their exhibition history with them.

My installations and sculptures are always very clearly defined and self-contained, with the placement of each element being fixed, but there is always an element of “adaptation” or decision-making occurring when shown somewhere else, balanced out with moments of fully trusting the work and letting the work go. To me, installation-based artworks always respond or react to the space they are being shown, so each new exhibition context feeds them, this is still an extremely exciting aspect. I love seeing the works being shown in dialogue with other pieces, which is also a privilege of working within the context of curated exhibitions, and then there are those moments of “care” happening in between: packing, unpacking, repacking the works for instance; checking if any damages happened, accepting the alteration of some colors, checking the instruction plans from time to time, feeding in spare parts, all this is part of an object-based sculptural practice such as mine, with all its material aspect and decision-making on when and what to let go in the history of the artwork.

The moment of the exhibition is a crucial moment for my practice: to me the artworks do not exist until the moment they are exhibited. While I can rely on an inventory of art- works following almost two decades of practice, my practice is pretty much connected to the infrastructures of storing and archiving my own practice. This exhibition pretty much pauses on that moment of “partially unveiling”, that thin in-between moment: between the transport crate and the moment of the exhibiting, holding onto the moment before the work actually becomes. In this exhibition, one also pauses on other aspects such as the materiality of the glass objects, the tension between materials, the fragility of unpacking and placing, the hierarchies between works with one work becoming the background for another, extracting them for a bit from the historical context they were developed for and looking at them for a second for what they are: language and form, containing many other stories of exhibitions within their materiality. Beth’s sound piece functions then almost like an ally agent, enhancing the factor of time inherent to the sound piece and perhaps even recalling the notion of time as an inherent component of an artwork that is about to shift into something else, a document perhaps.

Photo © Chroma

Bethan Hughes’ audiovisual installations, sculptures and texts interweave archival research and speculative narrative to explore the unnatural ecologies generated through industry, commerce and technology. Her work has been exhibited at venues including LABoral Centro de Arte y Creación Industrial, Gijón (SP), gnration, Braga (PT), Kunstpavillion, Innsbruck (AT), nGbK, Berlin (DE), Ars Electronica, Linz (AT), Haubrok Foundation, Berlin (DE), and HAUNT/frontviews, Berlin (DE). In 2023, she was a European Media Art Platform fellow and in 2024, she completed an Art & Ecology residency at MuseumsQuartier Vienna. She studied Fine Art at the Glasgow School of Art and Media Art at the Bauhaus-Universität Weimar and completed a PhD at the University of Leeds in 2020. She is currently working on her first monograph, forthcoming early 2025 with K. Verlag. Titled Elastic Continuum, it traces the material and symbolic transformations of a rubber-containing plant better known as the Kazakh dandelion.

Dominique Hurth is a visual artist working with installations, sculptures and editions. The starting point for new works is often a narrative that is present in places or images. Even though her installations often concentrate on the form, extensive and detailed research is firmly anchored in the development of this form. Her works have been exhibited in museums and art institutions internationally (including Palais de Tokyo, Paris; Fundació Tapies, Barcelona; Hamburger Bahnhof, Berlin; l’appartement 22, Rabat) and are part of several collections. She was the recipient of many prizes and residencies, including the Pollock-Krasner Foundation Grant (2016-17), the Prize of the Berlin Senate / Governing Mayor of Berlin at the ISCP, New York (2014), the Berlin Artistic Research Grant in the years (2022-23) and Villa Kamogawa, Kyoto (2025). Her latest book titled “Stutters”, published and commissioned by Printed Matter (NYC), was released in July 2021. It focuses on several years of archival research in the photo collection of the Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. In 2025 a solo exhibition in two chapters at the memorial of Ravensbrück will conclude her long-term investigation of the textile history and cultural appropriation of the female guard uniform (of the former concentration camp of Ravensbrück) with the support of the German Federal Cultural Foundation.

Neun Kelche is a project space curated by Kira Dell and Laura Seidel at Pasedagplatz in Berlin-Weißensee. In May 2024, the artist Neda Naujokaitė joined the team in the area of press and public and public relations and as assistant curator to the team. Since the beginning of 2021, local artists have found a space for exchange and encounters here. The program is shaped by the local community and developed further in collaborations on a national and international level. Neun Kelche works mainly with FLINTA* artists. In solo or duo exhibitions, site-specific installations are created, which are expanded performatively or with film/video/sound. The curatorial work of Kira Dell and Laura Seidel is based on a fundamentally power-critical and intersectional perspective. Thematically, they focus in particular on utopias of the planetary coexistence of human and non-human agents, ideas of collective love, social perspectives on parenthood and the potential for action of artistic materials. Instead of prescribing a rigid curatorial program, a collaborative negotiation process and in-depth studio visits are used to find thematic overlaps with artists and develop the exhibitions together. The Neun Kelche team takes a critical look at the working structures in the art world and the starting point of the curatorial work is to develop an exhibition program.

The exhibition is kindly supported by Hollweg Foundation and the Berlin Senatsverwaltung für Kultur und Gesellschaftlichen Zusammenhalt